The First Indochina War

In 1858, the French landed in Danang. By 1867, Vietnam had become a French colony, the “French Indochina” was established, comprising Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

During World War II, Vietnam was invaded by Japan. From then on, the Vietnamese fought to gain their independence, proclaimed in 1945.

A year later, the French attempted to reassert their authority, marking the beginning of the First Indochina War.

Uncle Giap: The Architect of Vietnam’s Military Victory

Ho Chi Minh created a rural base after attacking the French garrison. Ho Chi Minh (born Nguyễn Sinh Cung, 1890–1969) was a revolutionary leader, statesman, and the founding father of the modern Vietnamese nation. Deeply influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideology, he played a central role in Vietnam's struggle for independence from French colonial rule and later against American intervention during the Vietnam War.

In 1950, after defeating teh French at Cao Bang, he declared that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was the only legal government, recognised by China and the Soviet Union. Furthermore, he launched his offensive in the Red River valley after establishing the Workers Party, Lao Dong. Meanwhile, Eisenhower became the new U.S. president.

A Divided Country: The Split Between North and South

The Geneva Conference of 1954, after the decisive Battle of Dien Bien Phu, provided a ceasefire and divided the country into North and South parts along the 17th parallel. The French force withdrew from the North, and the Vietminh (Ho Chi Minh's men) from the South. The Chinese communists supported North Vietnam, while the United States supported South Vietnam. The Eisenhower administration, reluctant to abide by the Geneva agreement and concerned by the Communist menaces, began funnelling aid to Ngô Đình Diệm, who rejected the Geneva accords and proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam with himself as president.

Diệm’s Rule and U.S. Escalation

Diệm, a staunch anti-communist and Catholic in a largely Buddhist country, received strong support from the United States, which saw South Vietnam as a crucial front in the Cold War. The U.S. began sending advisors, military aid, and economic support, believing in the Domino Theory—that if one country in Southeast Asia fell to communism, others would follow.

However, Diệm’s authoritarian style, nepotism, and suppression of political and religious groups led to rising discontent. His brutal crackdown on Buddhist monks in 1963, widely publicized, further undermined his legitimacy. Diệm, a staunch anti-communist and Catholic in a largely Buddhist country, received strong support from the United States, which saw South Vietnam as a crucial front in the Cold War. The U.S. began sending advisors, military aid, and economic support, believing in the Domino Theory—that if one country in Southeast Asia fell to communism, others would follow.

However, Diệm’s authoritarian style, nepotism, and suppression of political and religious groups led to rising discontent. His brutal crackdown on Buddhist monks in 1963, widely publicized, further undermined his legitimacy.

That same year, with covert backing from the CIA, a military coup overthrew and assassinated Diệm. South Vietnam plunged into political instability, while the communist Viet Cong insurgency in the South intensified.

This chaotic period led the U.S. to deepen its involvement, setting the stage for full-scale American military intervention under President Lyndon B. Johnson after the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

In August 1964, just off the coast of North Vietnam, the U.S. destroyer USS Maddox was reportedly attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in what’s now known as the Gulf of Tonkin. A second attack was claimed two days later — though evidence remains unclear to this day.

Back home, President Lyndon B. Johnson used the incident to secure the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving him authority to escalate U.S. military involvement without a formal war declaration. In short: this moment opened the floodgates for the Vietnam War as we know it. In 1965, Johnson made a fateful decision: he committed U.S. ground troops to the conflict. What began as military "advisors" under Kennedy turned into a full-scale war under Johnson. By 1968, over 500,000 American troops were deployed in Vietnam.

From the jungles of the DMZ to the deltas of the South, America was suddenly at war in a foreign land with unclear goals and no end in sight.

"Americanizing" the War

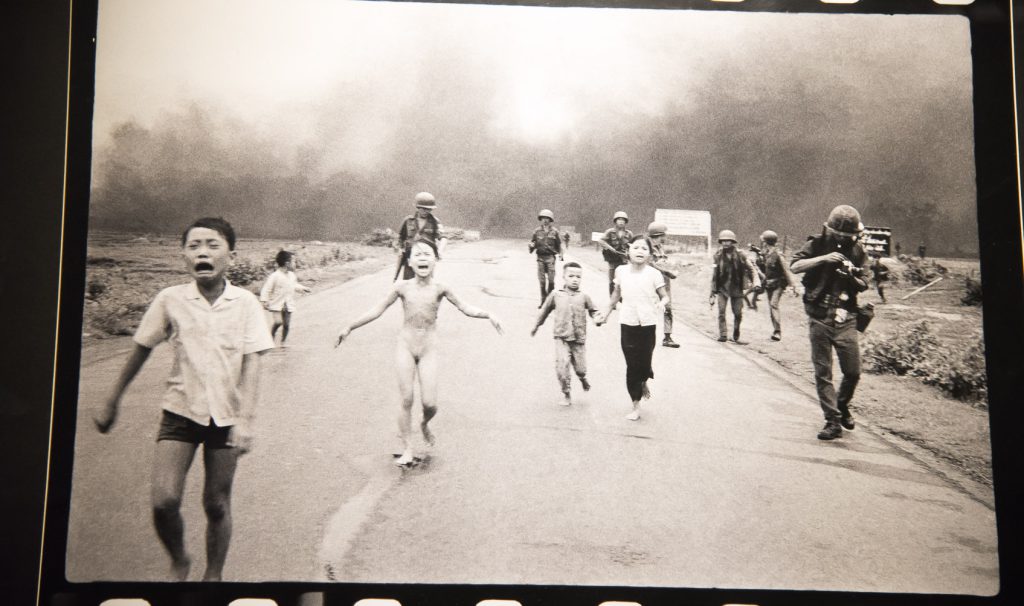

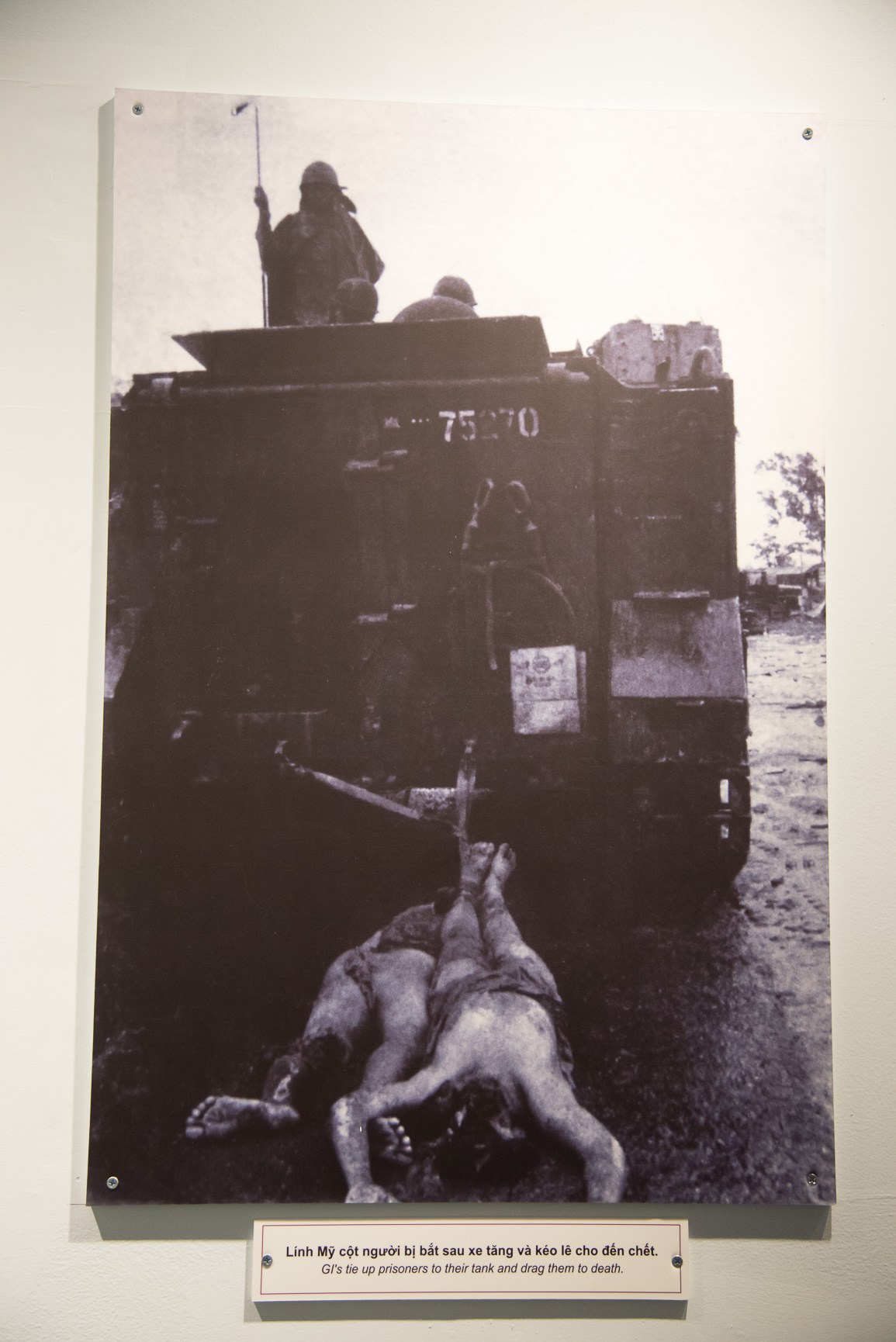

During the war, the population suffered from both the violence of the communist troops and the relentless American bombings. The damage caused by the incendiary bombs known as NAPALM was devastating, affecting not only the vegetation but, most tragically, the civilian population. It is stimed that the U.S. dropped 800,000 tons of bombs and used Agent Orange, a highly toxic defoliant herbicide, together with Napalm, an incendiary mixture made of petroleum.

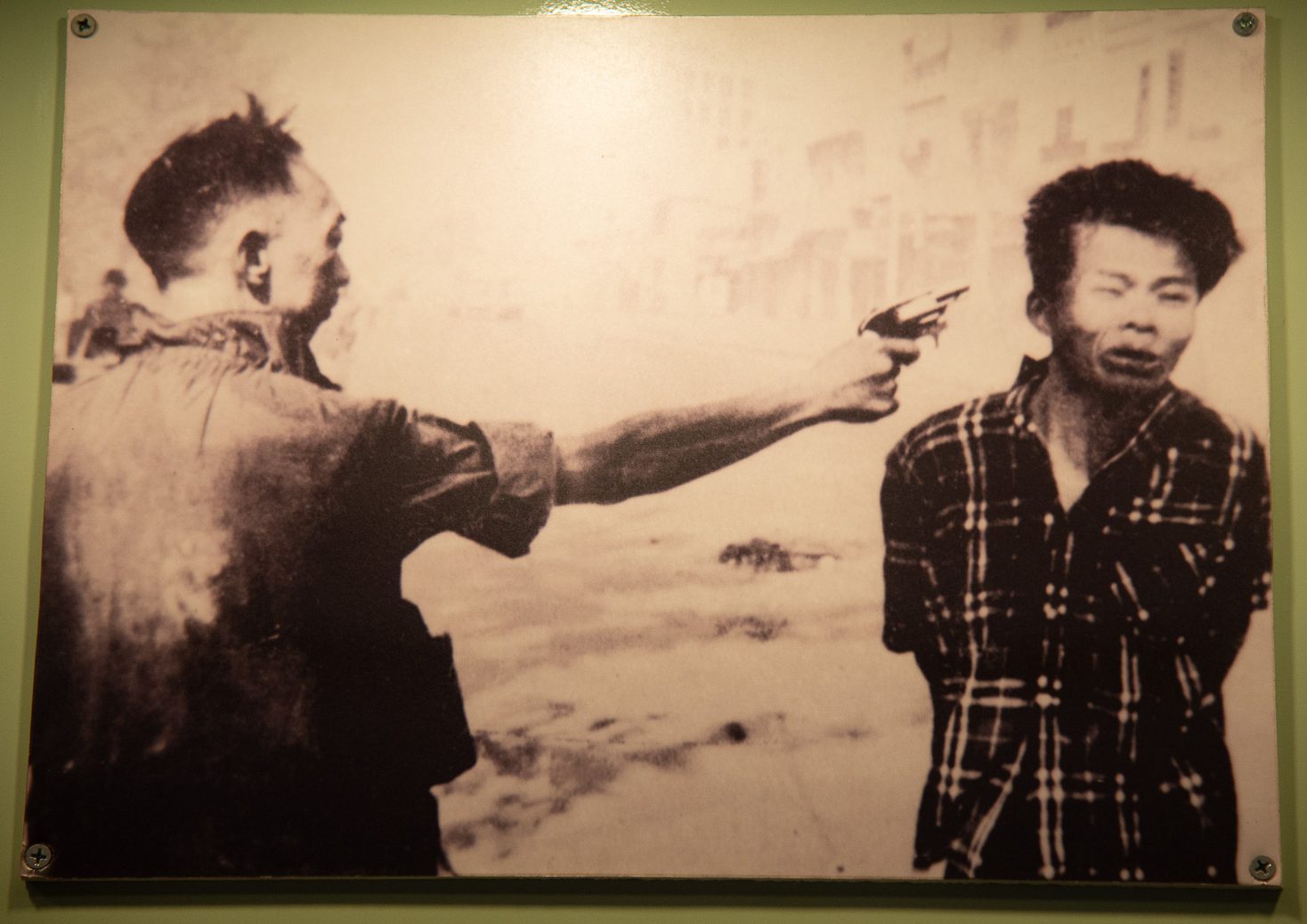

American troops had overwhelming air and missile superiority but they were unaccustomed to the tropical environment and climate. Despite technological superiority, American forces struggled with guerrilla warfare and unfamiliar terrain. Marines expecially struggled to distinguish civilians from combatants. Those who survived returned home deeply scarred by the war, often suffering from post-war psychosis.

The Cu Chi Tunnels near Ho Chi Minh City (a must-visit site today) show how the Viet Cong outmanoeuvred a much larger force through underground networks. Many soldiers were killed in ambushes. The North Vietnamese defended themselves from bombings by constructing vast underground cities at multiple depth levels, with the Vinh Moc tunnels being another notable example. They also hid traps in dense vegetation and employed guerrilla warfare tactics, receiving significant support from China and Russia.

The End of U.S. Involvement: Nixon’s Strategy and the Fall of Saigon

By 1969, Richard Nixon inherited a war that was deeply unpopular and seemed unwinnable. Determined to end American involvement, he introduced the concept of “Vietnamization”, which aimed to shift the burden of fighting from American soldiers to the South Vietnamese Army.

While the U.S. scaled down its direct involvement, Nixon continued bombing North Vietnam and extended the war into neighboring Cambodia and Laos in an effort to cut off supplies to the Viet Cong. This led to increasing protests and calls for a swift end to the conflict.

The Paris Peace Accords of 1973 finally brought a ceasefire agreement, marking the official withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. The North, however, continued to press for reunification, and the war was far from over.

Strategic Importance of the Ho Chi Minh Trail

The Ho Chi Minh Trail, also known as the Trường Sơn Trail, was a complex network of roads and paths that played a crucial role in the Vietnam War. Stretching over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia into South Vietnam, the trail was used primarily by North Vietnamese forces to send supplies, troops, and weapons to the Viet Cong in the South. It was a lifeline for the communist forces, but also a target for the U.S. military throughout the war. It provided an alternative route for moving soldiers, weapons, and supplies to the South, bypassing the heavily patrolled and bombed coastal routes.

The trail was essential for the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) because it allowed the South Vietnamese conflict to be sustained for years. Supplies such as ammunition, food, medical supplies, and tanks traveled along the trail, through Laos and Cambodia, and then into South Vietnam, despite constant U.S. airstrikes meant to disrupt its operation. The U.S. military recognized the trail’s significance early on and launched a sustained campaign to destroy it. Known as Operation Rolling Thunder and later Operation Linebacker, U.S. bombing raids targeted the Ho Chi Minh Trail from 1965 onwards.

Despite this intense bombing campaign, the North Vietnamese were able to repair the trail quickly, often under the cover of darkness.

The Fall of Saigon (1975)

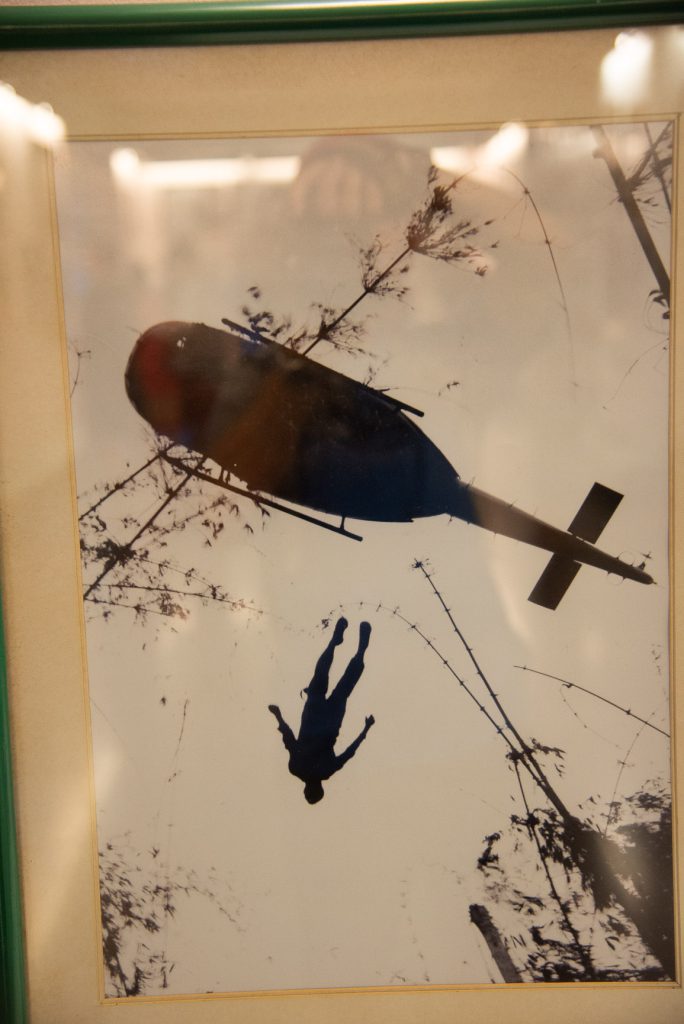

After the U.S. withdrawal, the South Vietnamese government, left to fend for itself, struggled against the advancing forces of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). On April 30, 1975, the North Vietnamese captured Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, marking the end of the war and the beginning of Vietnam's reunification under communist rule.

For many Americans, the fall of Saigon was a painful reminder of the war’s futility. For the Vietnamese, it was a moment of both celebration and hardship — a unified nation under a new government, but at great human cost.