Beyond the myth of prostitution: Geisha as artists, guardians of elegance, and symbols of Japanese tradition

When travelers first encounter the mysterious allure of Japan’s past, one of the most misunderstood topics is the role of women within entertainment and intimacy. Western fascination has often blurred the line between prostitution and the refined art of geisha, yet in truth, they belong to very different worlds.

Kamakura period (1185-1133)

During the Golden Age of samurai, the Kamakura period, prostitutes were playmates of the Heian nobles. Girls were trained in many skills, not only the erotic ones, to serve the warrior class and entertain the clients. We could say that from the beginning theatre and prostitution were connected.

The decree of Hideyoshi: the birth of the “Floating World” Ukiyo

In the Edo period (1603–1868), Japan saw the rise of the ukiyo—the “floating world”—urban districts devoted to pleasure, leisure, and art. Within these quarters, Kabuki theaters, tea houses, salons, and licensed brothels flourished. Prostitution was strictly regulated and confined to places such as Yoshiwara in Edo (modern Tokyo). From this system emerged a distinctive culture, one that echoed the elegance of the Heian tradition: sex and desire were reframed as refined courtship, a game of wit and allure between men and high-ranking courtesans.

It was a strictly hierarchical world. At the top stood the oiran, high-paid courtesans of elegance and prestige; at the bottom, the jorō, common prostitutes displayed behind wooden bars in shopfronts, or the yuna, who sold their bodies in the steamy haze of public baths.

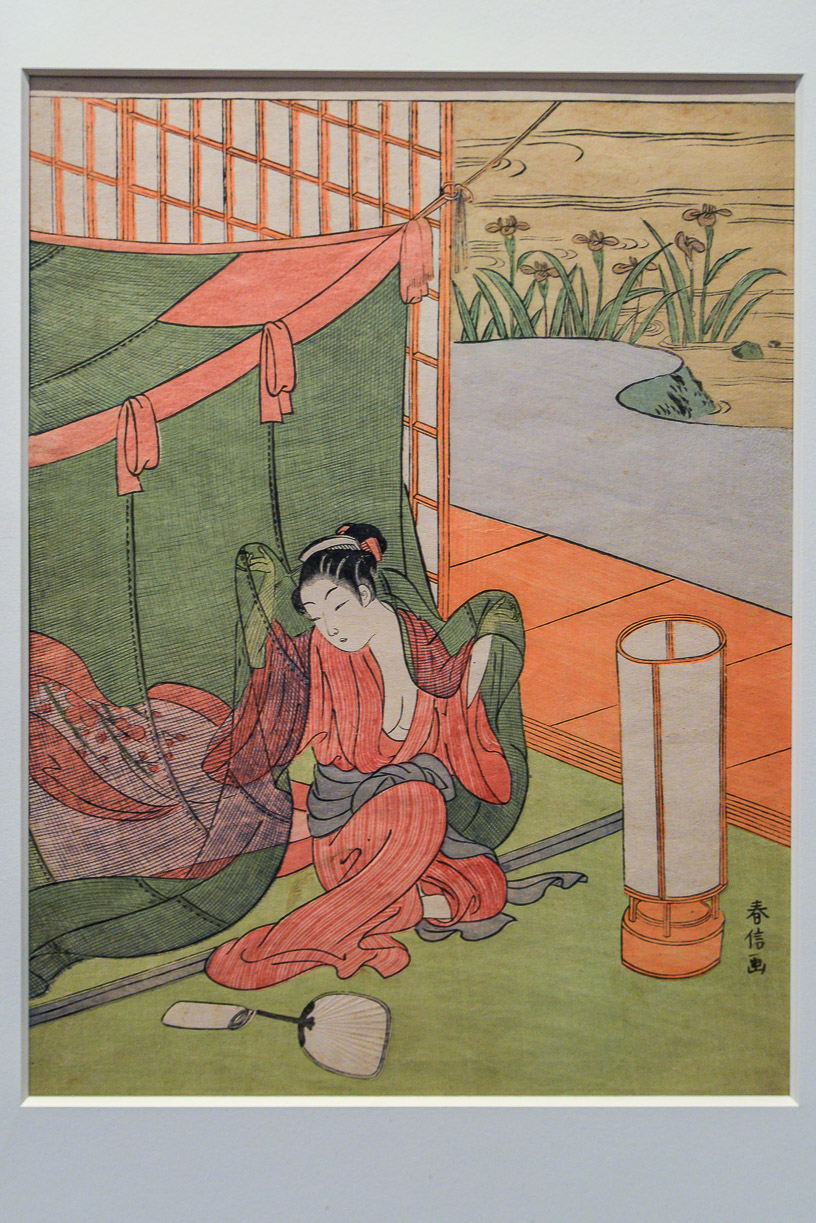

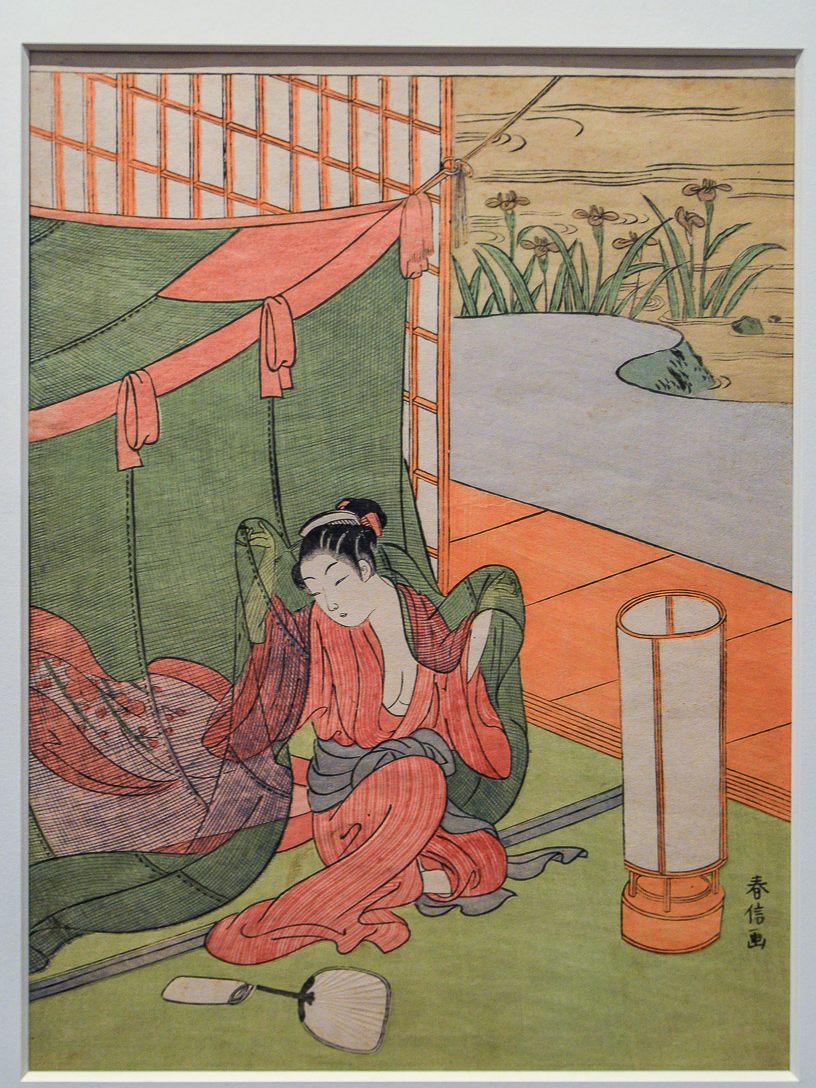

Among the oiran, the most exalted were the tayū—not only courtesans, but artists in their own right, celebrated as much for their artistry as for their beauty. These women were admired like actresses, idealized embodiments of femininity who often borrowed the names of noble ladies from the past. A tayū’s training was rigorous: poetry, calligraphy, dance, and music all formed part of her repertoire. Clients were entertained not through crude exchange, but through highly ritualized performances of courtship.

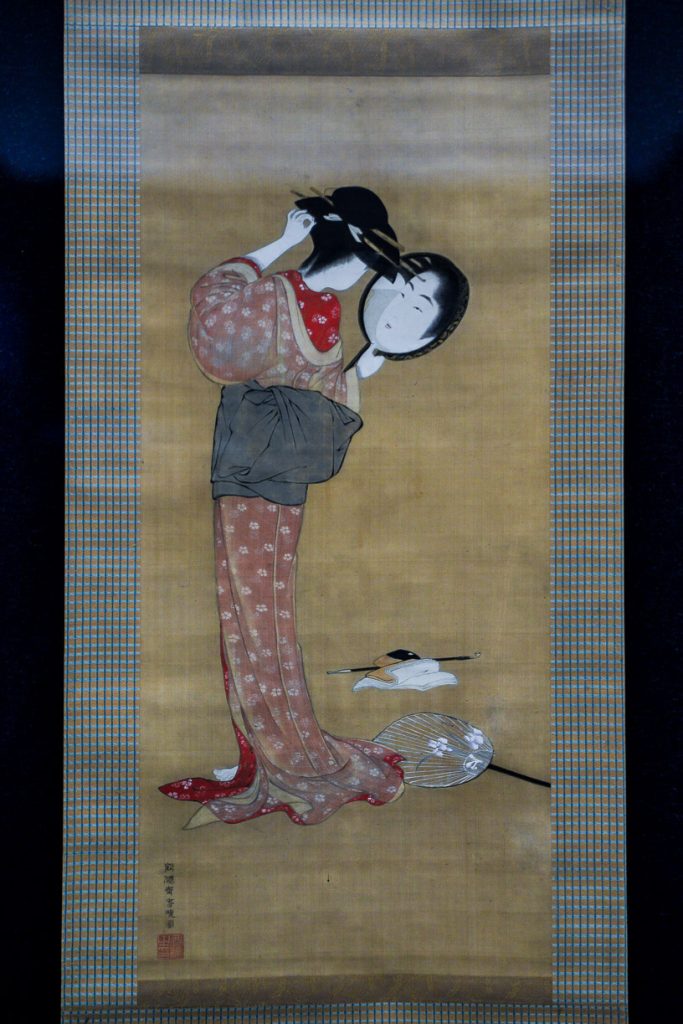

Her appearance was unmistakable: layers of extravagant kimono, a face painted in the iconic white of classical beauty, and a wide obi sash tied in front—a visible mark of her profession. She was both object of desire and cultural icon, a living artwork suspended between admiration and commerce, elegance and constraint.

“If Kabuki (theatre) was unexpectedly erotic, brothel could be described as theatre of love, where country girls masqueraded as sophisticated beauties and lowly merchants assumed the air of men of affairs.”

— Donald Shively

tayū in waiting

The geisha was not a prostitute but a symbol of aesthetic

In the early 1700s, geisha emerged, not as courtesans in the brothels, but as artists of the stage, enchanting audiences with music and song. Unlike their counterparts, the geisha’s world was never about sex; to cross that line would have threatened the delicate balance of the oiran’s domain.

Instead, they forged a different path, one measured not in commerce, but in artistry: the subtle mastery of music, the poetry of dance, the elegance of conversation, and the quiet grace that left every room they entered transformed.

Karyūkai, the “world of the flower and willow.”

The path of a geisha began almost in childhood. Some girls were born into an okiya, while others arrived there because poverty left their parents no choice. From as young as six, they stepped into this closed world, where an okaasan (“mother”) and an onesan (“older sister,” an experienced geisha) guided their every move.

As maiko, apprentices, they learned to dance, to play music, to speak with grace, and to move with elegance. Every gesture was a lesson, every moment a rehearsal for a life devoted to art. The cost of such training was immense. Elaborate kimono, intricate hairstyles, long years of education, all created a debt that weighed on their shoulders, repaid slowly once they began to work, their earnings shared with the house that raised them.

In Kyoto they were called geiko, and their lives unfolded in the hanamachi, the “flower towns”, where art and ritual flourished after nightfall. Together, these districts formed the karyūkai, the “world of the flower and willow.”

The Misunderstanding of Geisha

Geisha, in contrast to tayū, were never courtesans. They appeared slightly later, their role defined as strictly artistic. A geisha’s craft was performance: dance, music, conversation, and elegance. Unlike tayū, they were not meant to sell sex. Yet the two worlds overlapped. Both lived in the same districts, performed in the same teahouses, and wore lavish kimono. To the untrained eye, the distinction was nearly impossible to see.

Over time, however, geisha rose in prestige as guardians of refinement and tradition, while tayū gradually vanished by the eighteenth century.

Still, the confusion endured. It has roots in history, a story of blurred lines and foreign misinterpretation, and was further complicated by the practice of mizuage. For some apprentice geisha, or maiko, this coming-of-age ritual was intended to mark the passage into adulthood. But in certain eras and districts, it became a literal sale of virginity, with wealthy patrons paying vast sums for the “honour.” Not every geisha underwent this practice, yet the tales alone were enough to spark scandal and cement the misconception.

geisha with her maiko apprentice

woman dressed like a maiko

When Japan opened to the world in the 19th century, foreign visitors encountered this complex reality with little context. Writers and travelers often described geisha as “courtesans,” unable, or unwilling, to parse the subtle distinctions of the floating world. The image was further distorted during the American occupation after World War II, when prostitutes catering to soldiers began calling themselves “geisha girls.” By then, the stereotype had taken firm root.

Geisha today

The truth is more delicate. Geisha were, and remain, artists: women of discipline and elegance, guardians of a cultural heritage that valued refinement over seduction. Geisha still exist today, though far fewer young women choose, or are able to endure, the rigors of the geisha life. Moreover, geisha asobi, the experience of “playing with geisha”, has become an expensive pastime, and many modern clients no longer understand the rules of this subtle, highly codified art of entertainment.

In the end, what began as a theatricalized reflection of aristocratic life, especially the rituals of love and courtship, has, over time, become theater in its purest sense. Today, geisha performances are often reduced to stylized entertainment, designed for tourists seeking an exotic glimpse of “old Japan.”

Much like Kabuki, geisha endure as symbols and living memories of a tradition in which many of Japan’s aesthetic ideals are rooted: restraint, elegance, and refinement. Yet these carefully preserved performances, once the very essence of cultural sophistication, have also been absorbed into the currents of modern consumerism, the so-called “water business” (mizu shōbai).

Geisha remain, then, suspended between past and present, at once guardians of beauty and relics of a world transformed.

A geisha preparing her attire and makeup